Adrenal Gland Anatomy and Hormone Production

Feb 19, 2026

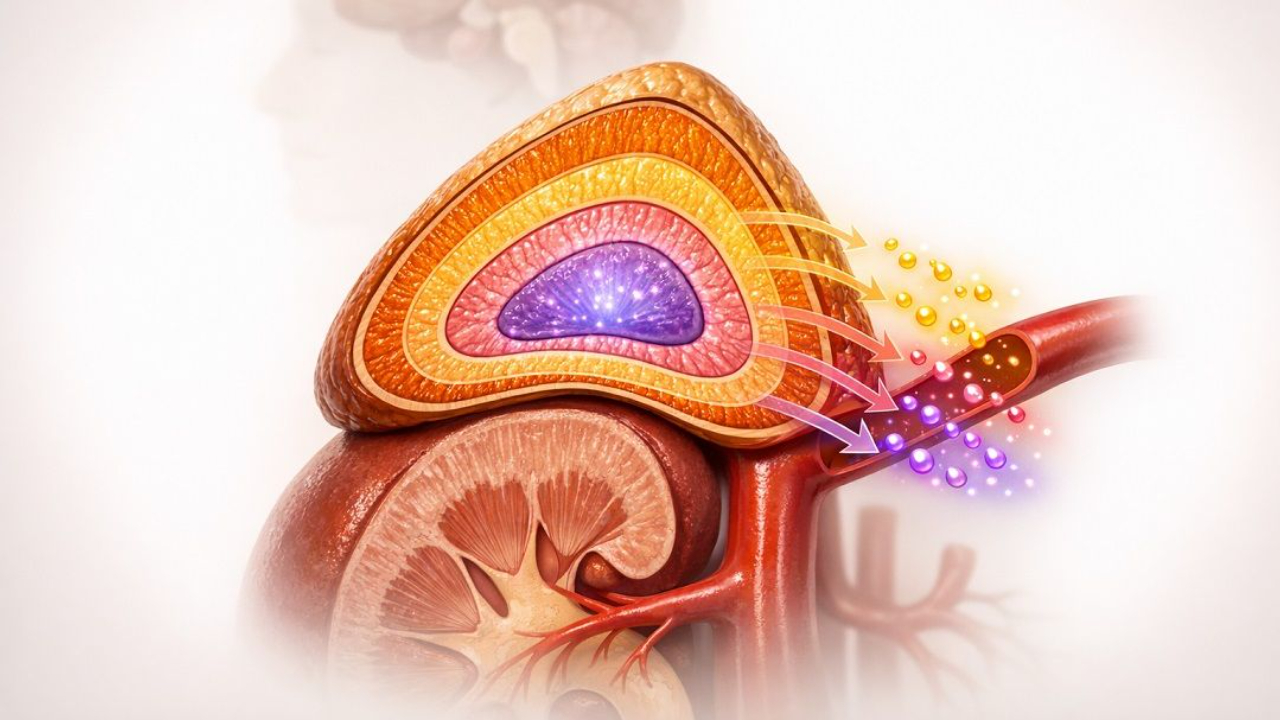

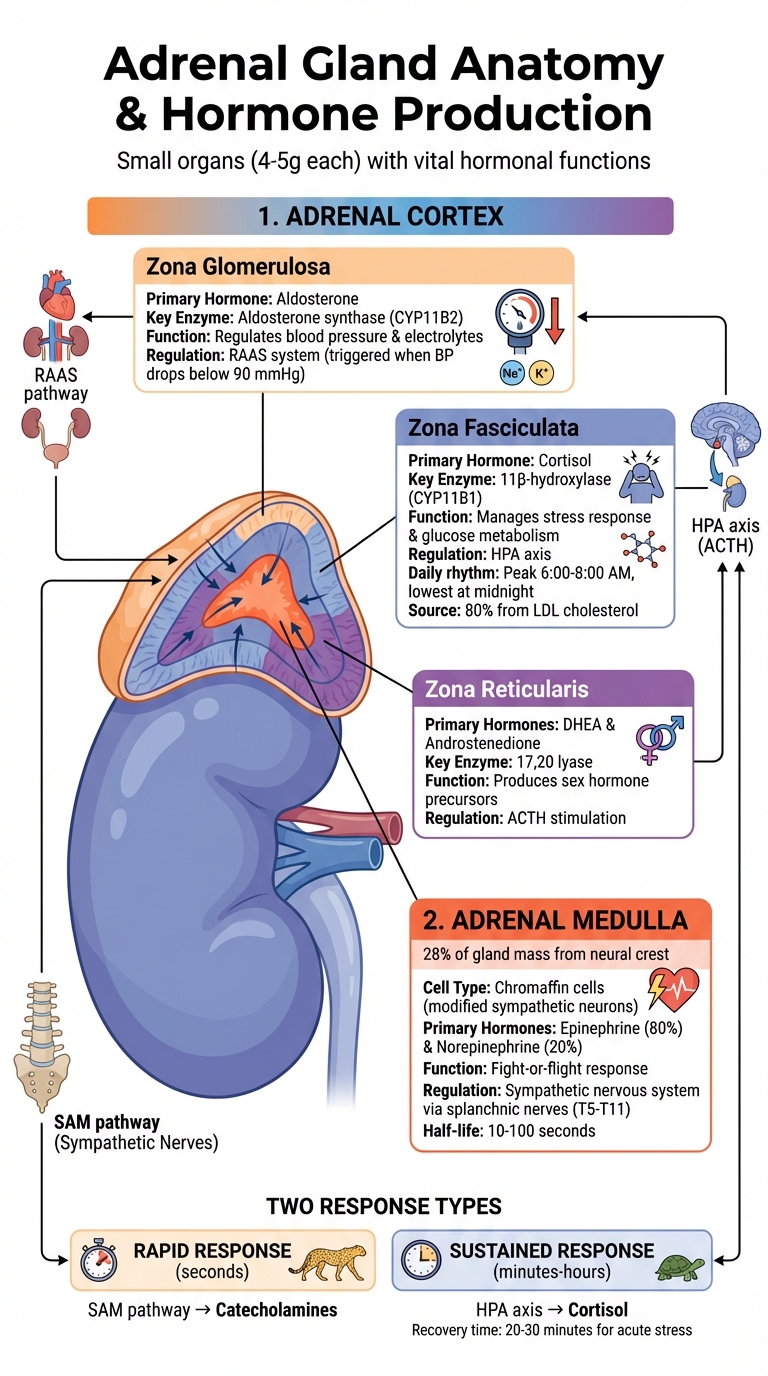

The adrenal glands, located above your kidneys, are small but vital organs that produce hormones essential for maintaining your body's balance. They consist of two main parts: the adrenal cortex (outer layer) and the adrenal medulla (inner core). Each has distinct roles and hormone outputs:

- Adrenal Cortex: Produces steroid hormones in three layers:

- Zona Glomerulosa: Secretes aldosterone, which regulates blood pressure and electrolytes.

- Zona Fasciculata: Produces cortisol, helping manage stress and metabolism.

- Zona Reticularis: Creates androgens, precursors for sex hormones.

- Adrenal Medulla: Releases catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) that trigger the "fight-or-flight" response during stress.

These glands are highly vascularized, ensuring hormones are distributed quickly. Their function is tightly regulated by systems like the HPA axis (for cortisol) and RAAS (for aldosterone). Chronic overactivation of these systems, leading to sustained elevations of cortisol and/or aldosterone, is associated with hypertension, metabolic changes, and suppressed immune function.

Understanding adrenal gland anatomy and hormone production is key for diagnosing and managing conditions like Addison's disease, Cushing's syndrome, and pheochromocytoma.

Adrenal Gland Anatomy: Cortex Zones and Hormone Production

What Adrenaline REALLY Does to Your Body

Adrenal Cortex: Zones and Hormones

The adrenal cortex consists of three distinct zones - zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis - each with its own enzyme profile that drives specific hormone production. This specialization allows the adrenal cortex to meet the body's diverse hormonal needs.

Zona Glomerulosa and Aldosterone

The zona glomerulosa, located at the outermost layer of the adrenal cortex, is the only zone that produces aldosterone. This is due to the presence of the enzyme aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) and the absence of 17α-hydroxylase, which prevents the synthesis of cortisol and androgens.

Aldosterone production is primarily controlled by the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) and blood potassium levels. When effective blood volume or renal perfusion pressure falls, the kidney releases renin, leading to angiotensin II formation and aldosterone secretion. High potassium levels also directly trigger aldosterone release, helping the body expel excess potassium.

"Aldosterone's classical epithelial effect is to increase the transport of sodium across the cell in exchange for potassium and hydrogen ions."

– Gordon H. Williams MD, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Hypertension, Brigham and Women's Hospital

Once released, aldosterone acts on the distal nephron in the kidneys to boost sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion. Since water follows sodium, this process also helps maintain blood volume and stabilize blood pressure.

Zona Fasciculata and Cortisol

The zona fasciculata is the largest layer of the adrenal cortex. Its cells, rich in lipids and arranged in straight bundles surrounded by capillaries, specialize in producing cortisol, the primary glucocorticoid.

Cells in this zone express enzymes like 17α-hydroxylase and 11β-hydroxylase, which convert cholesterol - sourced mainly (≈80%) from LDL - into cortisol.

Cortisol production is regulated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. When the body experiences stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), prompting the pituitary to release ACTH, which stimulates cortisol synthesis. Cortisol levels follow a daily rhythm, peaking between 6:00 AM and 8:00 AM and hitting their lowest point around midnight.

Cortisol plays a critical role in managing stress by increasing glucose production in the liver, enhancing vascular sensitivity to vasoconstrictors to maintain blood pressure, and suppressing inflammation and immune responses. However, chronically high cortisol levels can lead to muscle loss, bone weakening, weight gain, and even mood disorders like anxiety or depression.

This short video explains how the hypothalamus and pituitary gland coordinate hormone release to control the adrenal cortex.

The Endocrine System | The Hypothalamus & Pituitary Gland

Zona Reticularis and Androgens

The zona reticularis, the innermost layer of the adrenal cortex, produces adrenal androgens, mainly dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione. These hormones are synthesized with the help of the enzyme 17,20 lyase, which diverts steroid precursors toward androgen production instead of cortisol.

Adrenal androgens act as precursors that peripheral tissues and gonads convert into more potent sex hormones, such as testosterone and estrogens. In females, adrenal androgens provide a major contribution to circulating androgens and can be converted peripherally to testosterone, complementing ovarian production.

Like cortisol, androgen production is stimulated by ACTH, although these hormones are less involved in immediate stress responses.

| Zone | Primary Hormone | Key Enzyme | Main Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zona Glomerulosa | Aldosterone | Aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) | Regulates electrolyte balance and blood pressure |

| Zona Fasciculata | Cortisol | 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1) | Manages glucose metabolism and stress response |

| Zona Reticularis | DHEA / Androstenedione | 17,20 lyase | Produces precursors for sex hormones |

Blood flows centripetally from the outer capsule toward the medulla, distributing steroids and reinforcing the unique roles of each adrenal cortex zone.

Adrenal Medulla and Catecholamines

The adrenal medulla, distinct from the steroid-producing outer cortex, acts as a neuroendocrine hub. This inner portion - making up about 28% of the adrenal gland's mass - consists of chromaffin cells. These specialized cells are essentially modified postganglionic sympathetic neurons that operate exclusively as secretory cells. Their primary role is to produce and release catecholamines directly into the bloodstream, serving as a critical bridge between the nervous and endocrine systems. Here's a closer look at how this process works.

Chromaffin Cells and Hormone Synthesis

Chromaffin cells synthesize catecholamines starting with the amino acid tyrosine, which undergoes a series of enzymatic reactions. The first step involves tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme that converts tyrosine into L-DOPA. Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase then processes L-DOPA into dopamine within the cytoplasm. From there, dopamine is transported into secretory vesicles, where dopamine β-hydroxylase converts it into norepinephrine.

A unique aspect of this process occurs within the adrenal medulla itself. Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), an enzyme influenced by high local cortisol levels from the adrenal cortex, transforms norepinephrine into epinephrine. Typically, the adrenal medulla releases about 80% epinephrine and 20% norepinephrine. These hormones are stored in chromaffin granules alongside ATP and chromogranin A, ready for rapid release. Once released into the bloodstream, catecholamines have a short half-life of 10 to 100 seconds, ensuring quick but fleeting physiological effects.

Sympathetic Nervous System Connection

The adrenal medulla is directly connected to the sympathetic nervous system via preganglionic fibers traveling through the splanchnic nerves (T5–T11). When the body encounters stress, signals from the hypothalamus travel through the spinal cord, activating the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) pathway. This triggers preganglionic neurons to release acetylcholine, which opens calcium channels in chromaffin cells, leading to the exocytosis of catecholamine-filled granules.

This system supports the body's rapid stress response. Epinephrine has strong effects at both β‑ and α‑adrenergic receptors, with prominent β₁/β₂‑mediated increases in heart rate, cardiac output, blood glucose, and bronchodilation. Norepinephrine acts mainly on α₁ and β₁ receptors, causing vasoconstriction and increased blood pressure.Together, these hormones shift blood flow from non-essential areas like the digestive system and skin to critical regions such as the brain, heart, and skeletal muscles, preparing the body for immediate action.

Hormone Regulation and Stress Response

The adrenal glands are fine-tuned machines, constantly adjusting hormone production to adapt to stress. This precision relies on two key regulatory systems: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Together, they ensure cortisol and aldosterone levels align with the body’s needs.

HPA Axis and Cortisol Control

When the brain detects a threat, the stress response kicks into gear. The amygdala signals the hypothalamus, which releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). These hormones travel to the anterior pituitary, prompting the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream.

ACTH then binds to receptors in the adrenal cortex's zona fasciculata, sparking cortisol production. This process starts with the conversion of cholesterol into pregnenolone, a key step in cortisol synthesis. Once cortisol is released, it creates a feedback loop, signaling the hypothalamus and pituitary to reduce CRH and ACTH production. Inside target cells, cortisol binds to glucocorticoid receptors, influencing gene expression. This allows cortisol to regulate blood sugar, manage metabolism, and temporarily suppress non-essential functions during stress.

Meanwhile, the RAAS takes charge of aldosterone regulation.

How Your Brain Activates the Adrenal Gland

RAAS and Aldosterone Control

Aldosterone production is all about maintaining blood pressure and electrolyte balance. When blood pressure drops or the kidneys detect reduced blood flow, the juxtaglomerular apparatus releases renin. Renin converts angiotensinogen into angiotensin I, which is then transformed into angiotensin II by ACE.

Angiotensin II signals the adrenal cortex's zona glomerulosa to produce aldosterone by activating aldosterone synthase. As Meghan Dutt, Chase J. Wehrle, and Ishwarlal Jialal explain in StatPearls:

"Aldosterone synthase, which is present only in the glomerulosa and is regulated by angiotensin II, converts corticosterone into aldosterone."

Aldosterone works on the kidneys’ distal nephron to boost sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion. Water follows sodium, increasing blood volume and pressure. Additionally, high potassium levels can directly trigger aldosterone release, ensuring electrolyte balance.

What Weight Loss Does to Blood Pressure

Acute and Chronic Stress Responses

Stress responses unfold in two stages: the quick, immediate reaction and the slower, prolonged phase. The sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) axis handles the rapid response, releasing epinephrine and norepinephrine within seconds. In contrast, the HPA axis takes minutes to hours to elevate cortisol levels. For many brief stressors, autonomic and hormone levels begin returning toward baseline over the next 20–60 minutes, aided by parasympathetic activation, although the exact timing depends on the type and intensity of the stress and individual characteristics.

Chronic stress, however, is a different story. Prolonged activation of the HPA axis can lead to harmful effects. As Brianna Chu and colleagues highlight in StatPearls:

"If the exposure to a stressor is actually or perceived as intense, repetitive (repeated acute stress), or prolonged (chronic stress)... the stress response is maladaptive and detrimental to physiology."

Sustained high cortisol levels suppress the immune system by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and lymphocyte activity, leaving the body more vulnerable to infections and slower wound healing. Chronic stress also contributes to long-term health issues like high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, muscle loss, fat accumulation, and insulin resistance. These effects sharply contrast with the temporary benefits of acute stress, emphasizing the adrenal glands’ critical role in managing both short-term and prolonged stress.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways

Adrenal glands may be small (weighing just 4–5 grams), but their functions are anything but simple. Their unique structure - divided into the outer cortex and inner medulla - stems from distinct embryological origins: the cortex develops from mesodermal tissue, while the medulla originates from neural crest cells. This dual origin allows the adrenal glands to act as both endocrine organs and neuroendocrine hubs.

Each layer of the adrenal cortex has a specific role: the zona glomerulosa regulates electrolytes through aldosterone, the zona fasciculata manages metabolism via cortisol, and the zona reticularis produces androgens. Meanwhile, the medulla's chromaffin cells, which function as modified sympathetic neurons, release epinephrine and norepinephrine to handle immediate stress responses. Together, these regions enable the body to respond to stress in two ways: the medulla drives the fast-acting fight-or-flight response via the SAM pathway, while the cortex supports longer-term hormonal adjustments through the HPA axis and RAAS. This intricate system highlights the adrenal glands' critical role in balancing short-term and long-term physiological demands.

Clinical and Educational Applications

A solid grasp of adrenal anatomy and physiology is essential for both clinical practice and medical education. This knowledge is key to diagnosing conditions like Cushing's syndrome, Addison's disease, pheochromocytoma, and secondary hypertension. As StatPearls notes:

"In the diagnosis of disorders of the adrenal gland, a firm understanding of physiology is important given the different systems that regulate steroids".

For those interested in a hands-on learning experience, the Institute of Human Anatomy provides interactive courses using real human cadavers. These sessions offer a detailed look at adrenal anatomy and its relationships with nearby organs, which is especially useful for surgical planning. For instance, understanding the adrenal glands' vascular connections is crucial when addressing adrenal tumors, ensuring both safety and precision during procedures.

FAQs

What do the adrenal glands do during stress?

The adrenal glands play a crucial role in how your body handles stress. They produce important hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline, which are vital for several functions. These hormones help regulate metabolism and cardiovascular function and can temporarily adjust immune activity, enhancing some defenses while suppressing others, especially when levels remain high for long periods. This ensures your body can react swiftly and efficiently to stress while keeping essential processes in check.

What is the difference between the adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla in hormone production?

The adrenal glands consist of two distinct sections: the adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla, each with unique hormone-producing functions.

The adrenal cortex is responsible for producing steroid hormones. These include mineralocorticoids like aldosterone, which helps manage sodium and potassium levels, and glucocorticoids like cortisol, which supports metabolism and the body’s response to stress. Additionally, the adrenal cortex produces small amounts of sex hormones.

On the other hand, the adrenal medulla generates catecholamines, such as adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine). These hormones are central to the "fight-or-flight" response, preparing the body to handle stress by increasing heart rate, boosting blood pressure, and enhancing energy availability.

What health problems can arise from overactive adrenal glands?

When your adrenal glands stay overactive for too long, it can cause a variety of health problems. These include medically recognized conditions such as Cushing’s syndrome (excess cortisol), primary aldosteronism (excess aldosterone), and catecholamine-secreting tumors like pheochromocytoma, which can lead to high blood pressure, changes in metabolism, and alterations in immune function. The culprit behind these problems is often the excessive production of hormones like cortisol and adrenaline.

One major factor behind prolonged adrenal activity is chronic stress. Over time, constant stress can take a toll on your body, making it harder to stay healthy and balanced. Finding ways to manage stress and consulting with a healthcare professional can go a long way in preventing more serious complications.