Understanding Muscle Fiber Types: Exercise and Muscle Performance Insights

Jan 11, 2026

Introduction to Endurance Exercise: The Key to Building Muscle

Do you know why your muscles feel sore after a tough workout or why they seem to get stronger over time, contributing to skeletal muscle hypertrophy? It’s because muscles are incredibly adaptable, designed to respond to challenges by rebuilding themselves better than before. When you push your body through exercise, tiny tears form in the muscle fibers. Don’t worry, that’s a good thing for promoting muscle hypertrophy and building muscle! Your body repairs these tears, making the muscles thicker and stronger, a process called hypertrophy training. But that’s not all. Beneath the surface, your muscles undergo lesser-known changes, like developing better endurance or learning to fire more efficiently depending on how you train. Curious about what makes this possible, or how fast and slow-twitch muscle fibers play a role? Stick around, because we’re diving deep into the fascinating science behind these powerhouse structures.

Strength vs Hypertrophy: The Science of How to Build Muscle

How Muscles Are Structured

Muscles are the engines that drive human movement, allowing us to perform everything from the simplest gestures to the most complex athletic feats. To truly understand how they work, we must first dive into their structure and organization. Muscles are highly specialized tissues, composed of intricate components working in harmony to produce changes in muscle force and movement, ultimately influencing human skeletal muscle performance. Let's break down the basics of skeletal muscle structure before exploring its finer details.

The Basics of Skeletal Muscle and Muscle Growth

Skeletal muscles are one of the three primary types of muscle in the body, alongside cardiac muscle (found only in the heart) and smooth muscle (present in organs like the stomach and blood vessels). Unlike the other two types, skeletal muscles are unique because they are voluntary, meaning you control their movement consciously. Their primary role is to move and stabilize the skeleton, making them essential for locomotion, posture, and general activity. These muscles are attached to bones via connective tissues called tendons, forming the system that powers every deliberate motion. Skeletal muscles are also distinct in appearance; under a microscope, they have a striated (striped) pattern due to their internal structure. This organization is what allows them to generate the precise, powerful contractions needed for movement.

Anatomy of a Muscle and Muscle Fiber Type

At the macro level, a muscle, such as the biceps brachii in your upper arm, appears as a single entity, but the anatomy of its muscle fibers determines its overall performance. However, it is, in fact, a highly organized collection of smaller units. The building blocks of a muscle are called muscle fibers, which are the individual cells that contract and generate force, playing a crucial role in muscle mass.

Muscle Fibers vs. Muscle Cells

Muscle fibers are often referred to as cells because they share many of the characteristics of traditional cells, such as a membrane, cytoplasm, and organelles that are crucial for muscle tension. However, they are distinct in their structure and function. Unlike most cells, muscle fibers are long and cylindrical, sometimes spanning the entire length of the muscle, which contributes to an increase in muscle strength. They are also multinucleated, meaning they contain multiple nuclei to support their high metabolic demands, and the proteins are added to the muscle to enhance performance.

Organization of Fibers Within the Muscle

Muscle fibers are grouped into bundles known as fascicles, which are surrounded by a layer of connective tissue called the perimysium. Within each fascicle, the muscle fibers themselves are encased in a delicate sheath called the endomysium, providing individual support and nourishment.

Attachment to the Skeleton

At both ends of a skeletal muscle, the fibers converge into tendons, which are made of dense connective tissue that supports muscle force. Tendons anchor the muscle firmly to bones, creating a system that translates muscle contraction into movement. For example, when the biceps brachii contracts, it pulls on the tendons attached to the forearm bones, causing your arm to bend at the elbow. Through this elegant combination of fibers, fascicles, and tendons, skeletal muscles achieve the remarkable balance of strength, flexibility, and precision that defines human motion, enhancing muscle activation. This layered structure not only allows them to contract efficiently but also provides the durability needed to endure repeated use.

Having mentioned the functional relationship between muscles and tendons, you might find it interesting to explore their roles and structures further in our blog Muscle vs Tendon: Key Differences Explained.

Types of Muscle Fibers

Muscle fibers, the essential units of skeletal muscle tissue, are not all alike and can affect individual muscle performance, particularly with changes in fiber type. Depending on their characteristics and functions, individual muscle fibers can be classified into distinct types, each tailored to specific physical demands. This diversity in muscle fibers allows the human body to excel in both aerobic and anaerobic training activities.

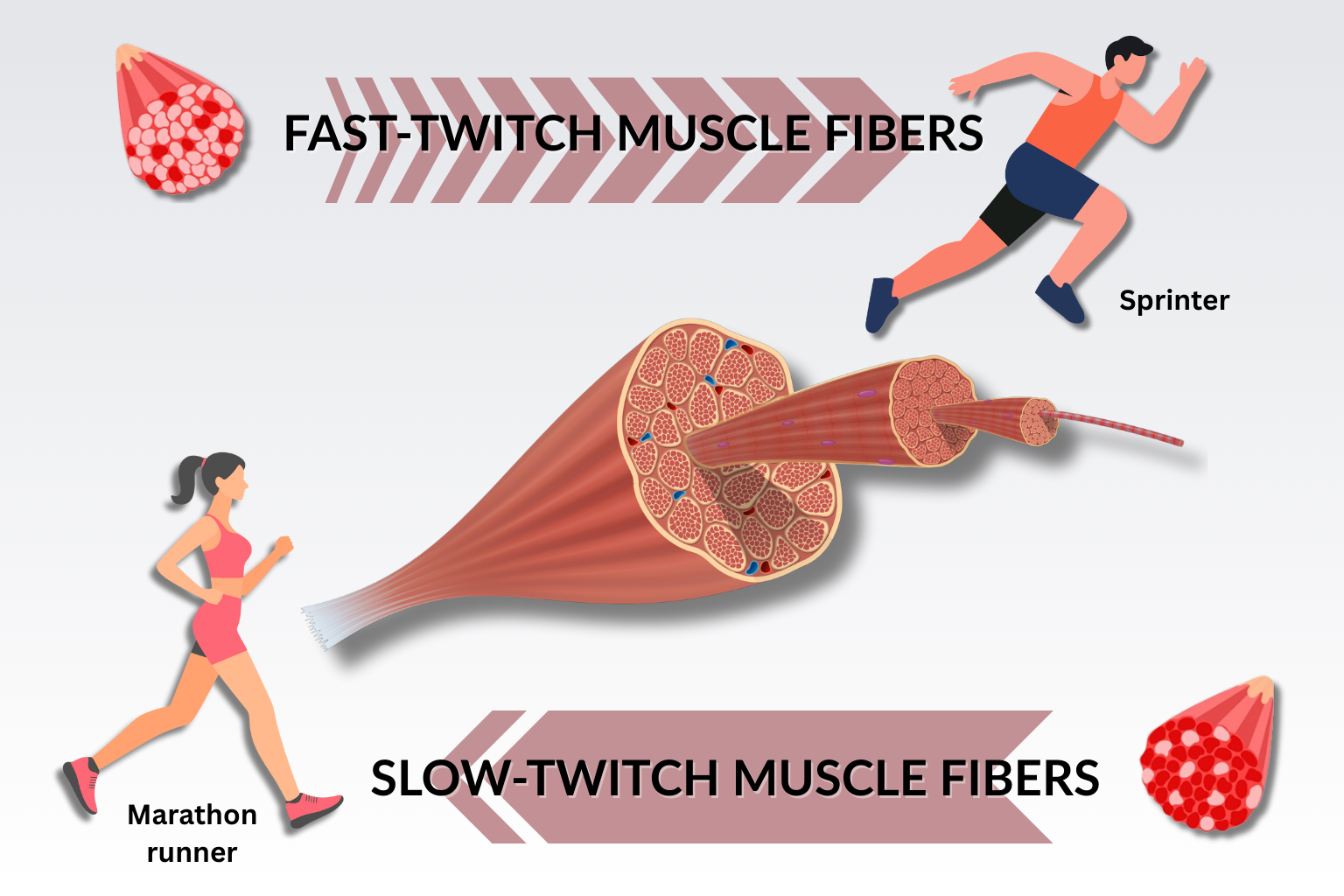

Fast vs. Slow Twitch Muscle Fibers

Muscle fibers are broadly categorized into two primary types: fast-twitch and slow-twitch fibers. Each type of muscle group is uniquely suited to different activities and energy demands. Fast-twitch fibers, known as Type II fibers, are built for rapid, explosive movements. They generate a high amount of force in a short time but fatigue quickly. On the other hand, slow-twitch fibers, referred to as Type I fibers, are designed for sustained, endurance-based activities. They contract more slowly and produce less force than fast-twitch fibers but have a remarkable ability to resist fatigue. Fast-twitch fibers are further divided into Type IIa and Type IIb fibers. Type IIa fibers, also called intermediate fibers, combine some of the endurance traits of slow-twitch fibers with the power and speed of Type IIb fibers. This intermediate quality makes them adaptable for both aerobic and anaerobic activities, enhancing muscle and performance. Type IIb fibers, however, are pure powerhouses, optimized for short bursts of intense activity, such as sprinting or weightlifting, with minimal endurance capability, which influences the overall mass of the muscle.

Slow-twitch fibers rely heavily on oxygen to generate energy, making them ideally suited for aerobic activities. In contrast, fast-twitch fibers, or fast fibers, depend more on anaerobic processes, using stored energy sources like glycogen for quick bursts of power, which can produce changes in muscle performance and lead to changes in fiber type. This fundamental difference in energy utilization underpins their distinct roles in movement and athletic performance, highlighting the importance of different types of exercise for muscle development.

Activities and Fiber Engagement

The type of muscle fiber engaged during physical activity depends on the nature and intensity of the exercise. Activities that demand sustained effort over long periods primarily rely on slow-twitch fibers. For instance, marathon running is a classic example where slow-twitch fibers dominate, as they provide the endurance needed to maintain a steady pace for hours. Similarly, activities like yoga or long-distance cycling also heavily recruit these fibers, emphasizing their ability to resist fatigue and support prolonged effort.

In contrast, fast-twitch fibers come into play during high-intensity, short-duration activities that require explosive power. Sprinting, for example, demands rapid, forceful contractions that only fast-twitch fibers can deliver, showcasing the increase in muscle fiber recruitment. Likewise, exercises like heavy weightlifting or plyometric jumps rely on these fibers to generate the significant force needed to lift or propel the body quickly. The intermediate Type IIa fibers are engaged in activities that fall between these two extremes, such as soccer or basketball, which require both bursts of speed and sustained effort, highlighting the role of Type IIa and Type IIb fibers.

Slow-Twitch Muscle Fibers

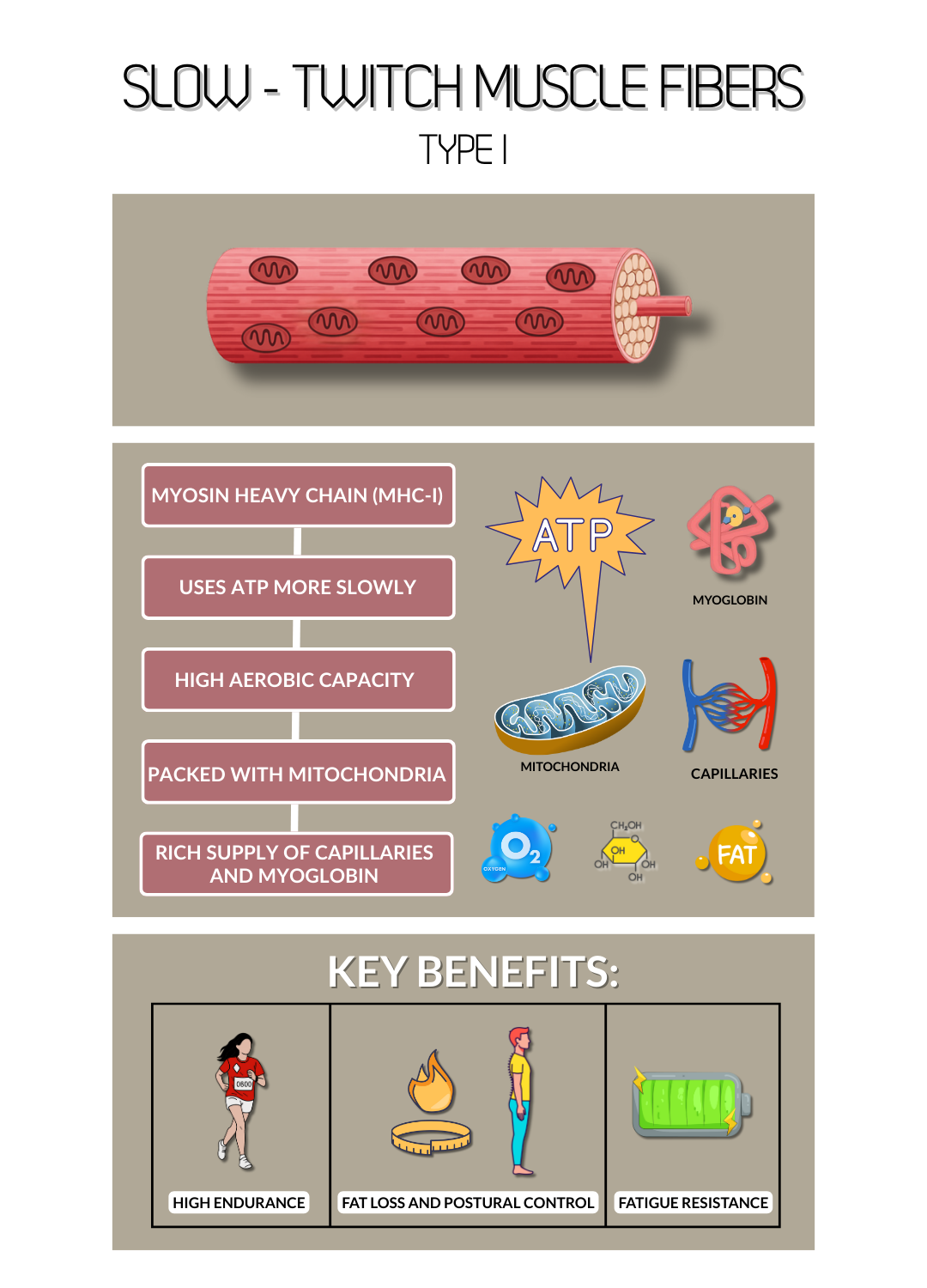

Slow-twitch muscle fibers, or Type I fibers, are the workhorses of endurance activities. They are specialized for efficiency and prolonged use, making them essential for tasks that demand sustained effort. While they may lack the explosive power of fast-twitch fibers, their unique features make them indispensable for activities requiring stamina and resilience, contributing to overall changes in muscle composition.

Features and Functions

Slow-twitch fibers are characterized by their high aerobic capacity, which means they rely heavily on oxygen to produce energy, preventing loss of muscle mass during endurance activities and reducing the risk of muscle injury. This energy is synthesized in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal energy currency of the body. Slow-twitch fibers are densely packed with mitochondria, the cellular organelles responsible for energy production. These mitochondria use oxygen, delivered via the bloodstream, to efficiently generate ATP through a process called aerobic respiration, vital for type I muscle fibers. The oxygen delivery system in slow-twitch fibers is highly developed. These fibers have an extensive network of capillaries, which ensures a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients. Additionally, they are rich in myoglobin, a protein that binds and stores oxygen within the muscle cells. Myoglobin not only facilitates oxygen transport within the fiber but also gives slow-twitch muscles their distinct red color. This combination of capillary density, abundant myoglobin, and numerous mitochondria allows slow-twitch fibers to sustain activity over long periods without fatiguing.

Advantages and Limitations

The primary advantage of slow-twitch fibers lies in their resistance to fatigue. This makes them ideal for endurance-focused activities such as long-distance running, swimming, or cycling, where specific muscle adaptations are crucial. They are also critical for maintaining postural stability, as muscles responsible for holding the body upright must be able to sustain low levels of contraction over extended durations, which is important for endurance exercise. However, the endurance capabilities of slow-twitch fibers come at the cost of force production. These fibers contract more slowly and generate less force compared to fast-twitch fibers, which are crucial for the overall mass of the muscle. This trade-off means they are not suited for explosive movements or activities requiring quick, powerful bursts of energy. For instance, while a slow-twitch fiber excels during a marathon, it would struggle to contribute significantly in a sprint, leading to decreased performance and muscle appearance due to the specific muscle demands of each activity. Despite these limitations, slow-twitch fibers play a crucial role in physical fitness and overall health. Their ability to sustain prolonged activity helps improve cardiovascular health, metabolic efficiency, and endurance capacity, all of which contribute to long-term physical well-being.

For an in-depth guide on addressing imbalances and correcting posture, you can read our 5 Anatomical Insights Every Fitness Trainer Needs to Design Safer Workouts blog.

Adaptations to Exercise and Resistance Training

One of the remarkable qualities of slow-twitch fibers is their ability to adapt to regular exercise. Endurance training, such as running or cycling, induces physiological changes that enhance the performance of these fibers. Over time, the capillary density surrounding slow-twitch fibers increases, improving oxygen and nutrient delivery. This adaptation allows the muscle to sustain activity for longer durations without fatiguing. Additionally, endurance training stimulates an increase in myoglobin content, which enhances the muscle's oxygen storage and transport capacity. The size and number of mitochondria within the fibers also grow, boosting the muscle's ability to produce ATP aerobically, which is vital for endurance exercise. These changes collectively enhance the muscle's efficiency, allowing it to generate energy more effectively and sustain activity with less fatigue. These adaptations are not limited to elite athletes. Anyone who engages in regular aerobic exercise can experience improvements in slow-twitch muscle function. This makes endurance training an essential component of any fitness regimen, promoting not only athletic performance but also overall health and vitality.

In short, slow-twitch fibers may not be as flashy or powerful as their fast-twitch counterparts, but they are the unsung heroes of endurance and stamina. Their unique structure, high aerobic capacity, and ability to resist fatigue make them indispensable for sustained physical activity. Through regular training and exercise, these fibers can be further optimized, enhancing their already impressive endurance capabilities and contributing to a healthier, more active lifestyle.

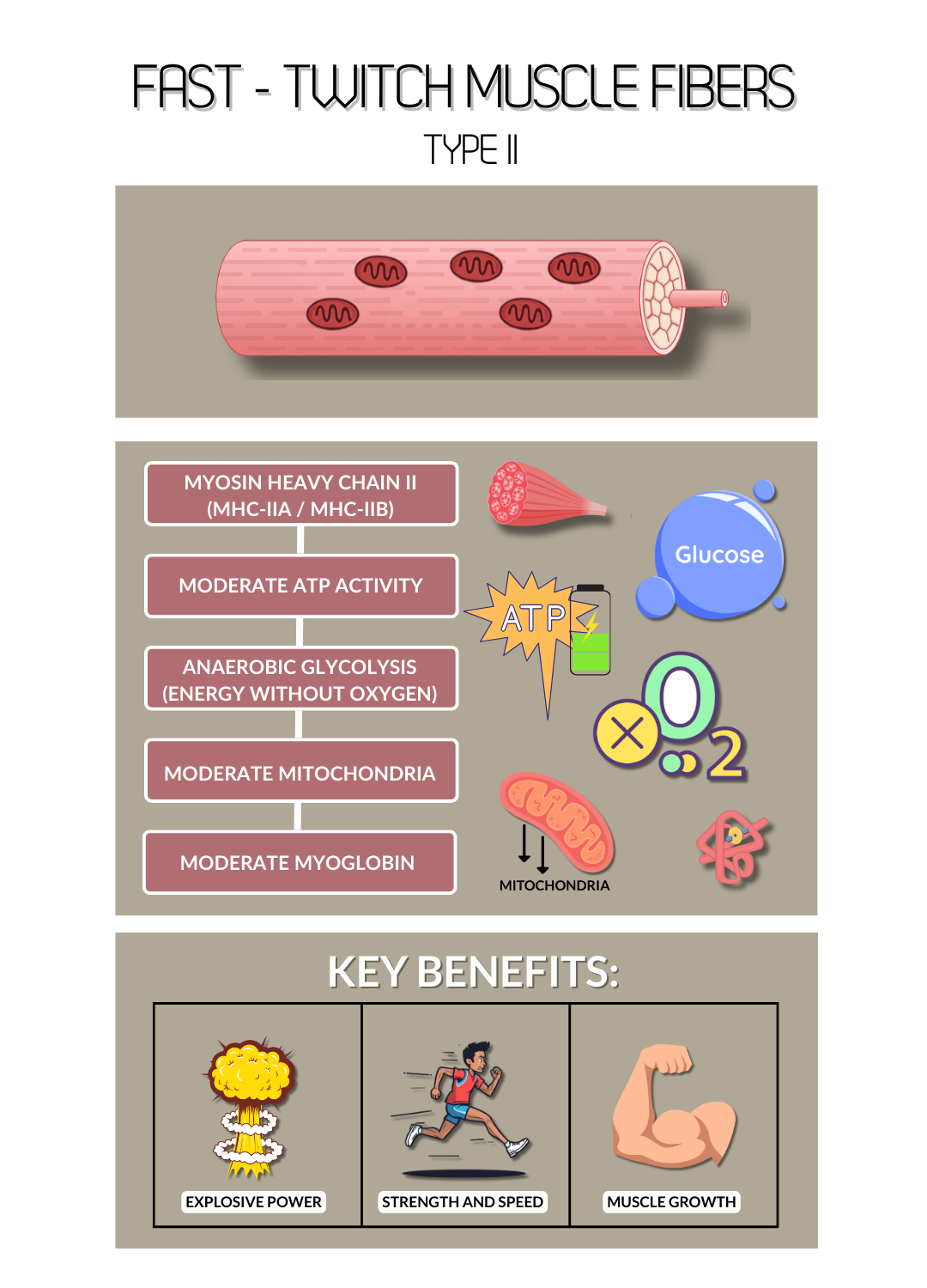

Fast-Twitch Muscle Fibers

Fast-twitch muscle fibers are designed for rapid, powerful movements, which are essential for increasing muscle size during high-intensity exercise. These fibers are particularly suited to activities that require explosive force but only for short bursts of time. Their specialized characteristics allow them to generate large amounts of power quickly, but they come with some trade-offs in terms of endurance and can lead to proteins being lost and muscle mass decreasing. Fast-twitch fibers are the cornerstone of sprinting, heavy lifting, and any athletic pursuit that demands speed and strength over a short period.

Features and Functions

One of the most noticeable features of fast-twitch muscle fibers is their larger diameter compared to slow-twitch fibers, contributing to an increase in muscle size. This greater size allows them to produce a higher force output when contracting. Fast-twitch fibers are capable of rapid and intense contractions, but they rely on anaerobic energy pathways for energy production, which can affect individual fiber performance. Unlike slow-twitch fibers, which depend heavily on oxygen to generate ATP, fast-twitch fibers primarily use glycolysis, a process that breaks down glucose into pyruvate to generate energy without the need for oxygen. In addition to glycolysis, fast-twitch fibers store large amounts of glycogen, a polysaccharide that serves as a quick-release form of energy. Glycogen is stored within the muscle cells and is rapidly converted into glucose, which can be used by the body during intense physical activity to support muscle mass. This makes fast-twitch fibers particularly well-equipped for short, high-intensity bursts of energy, such as sprinting, jumping, or lifting heavy weights, which can lead to an increase in muscle fiber size. These fibers also rely less on mitochondria and capillaries than slow-twitch fibers because they do not need as much oxygen or endurance-based systems for energy production, affecting changes in muscle performance.

Advantages and Limitations

The primary benefit of fast-twitch fibers is their ability to generate quick, powerful movements, significantly impacting the overall mass of the muscle. Because of their larger size and reliance on anaerobic energy systems, they can produce high amounts of force in a very short period. This is essential for actions that demand explosive strength, such as sprinting, jumping, or performing a high-intensity resistance exercise like powerlifting. However, the main drawback of fast-twitch fibers is their lower endurance. Since they rely on anaerobic energy systems, which are less efficient in terms of ATP production, fast-twitch fibers fatigue more quickly than slow-twitch fibers. The rapid depletion of glycogen stores during sustained activity leads to muscle fatigue, which is why these fibers are not suited for long-duration activities and can result in muscle atrophy due to age. For example, after a few seconds of intense sprinting or heavy lifting, fast-twitch fibers can quickly become depleted, requiring a recovery period before they can perform at their peak again.

Adaptations to Exercise and Endurance Training

Training can significantly enhance the capacity of fast-twitch fibers, especially for activities requiring speed, strength, or explosive power, leading to an increase in muscle mass. Through consistent high-intensity training, such as sprinting or weightlifting, fast-twitch fibers can adapt by increasing glycogen storage capacity. This allows muscles to perform better during short, intense bursts of activity before glycogen stores become depleted. In addition to enhanced glycogen storage, fast-twitch fibers also benefit from increased power and velocity of muscle contractions, contributing to overall muscle strength. Training techniques like plyometrics or sprint intervals can promote neural adaptations, leading to quicker and more efficient recruitment of fast-twitch fibers during high-intensity efforts. These adaptations make athletes more explosive and capable of achieving greater performance in their chosen sport or activity.

The Role of Oxygen and ATP Production

ATP, or adenosine triphosphate, is the energy currency of the body, essential for muscle performance and building muscle mass. The production of ATP is essential for muscle contraction, and how ATP is generated differs depending on the presence or absence of oxygen, which influences muscle hypertrophy and the cross-sectional area of muscle fibers. Understanding these processes helps explain how muscles perform during various physical activities and how energy systems affect performance during exercise.

Aerobic vs. Anaerobic Energy Systems

The human body relies on two primary energy systems to produce ATP: the aerobic and anaerobic systems, both crucial for building muscle cross-sectional area. The difference between these two systems lies in the presence of oxygen. The aerobic energy system is the more efficient of the two, especially in supporting type I muscle fibers. In this system, oxygen is used to metabolize carbohydrates, fats, and proteins to produce ATP. This occurs in the mitochondria of muscle cells through processes such as the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. The result is a large yield of ATP, up to 36 ATP molecules per glucose molecule, which makes the aerobic system ideal for sustained, lower-intensity activities such as long-distance running or cycling. In contrast, the anaerobic energy system does not rely on oxygen, which can lead to muscle atrophy if not balanced with aerobic activities. Instead, ATP is generated through glycolysis, a process that breaks down glucose into pyruvate, yielding 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule to support muscle activity. Although this is a much lower yield compared to the aerobic system, it occurs rapidly and is ideal for short bursts of high-intensity activity. Anaerobic metabolism is predominant in activities like sprinting, heavy lifting, and other forms of explosive exercise where rapid energy release is essential for maintaining muscle tension.

Efficiency and Trade-offs

The main trade-off between the two systems is speed versus efficiency. The anaerobic system is fast, providing quick energy for short bursts, but it produces far less ATP per molecule of glucose. As a result, anaerobic activities can only be sustained for a short period before muscle fatigue sets in due to the depletion of energy stores, which can lead to muscle damage. On the other hand, the aerobic system is much more efficient at generating ATP, making it suitable for long-duration activities that enhance muscle activation. However, it takes time for oxygen to be delivered to muscle cells and for the metabolic processes to produce ATP, which is why aerobic activities are generally lower in intensity compared to anaerobic activities. The differences in ATP production underlie the reason why fast-twitch fibers prioritize speed over endurance, essential for enhancing muscle performance. These fibers primarily rely on anaerobic pathways for quick bursts of energy, even though it means sacrificing long-term endurance. In contrast, slow-twitch fibers are optimized for endurance due to their reliance on aerobic pathways, allowing them to produce ATP more efficiently and sustain activity over longer periods.

Supporting Muscle Adaptations Through Nutrition and Strength Training

Proper nutrition is essential for optimizing muscle performance and supporting the adaptations that occur during exercise. Without adequate fuel, the body cannot perform at its best or recover properly, which can impair muscle growth and athletic progress. The right combination of nutrients plays a crucial role in both energy production and muscle recovery, making nutrition a key component of an effective fitness regimen.

Importance of Fueling Muscles

The body requires a wide range of nutrients to fuel muscles effectively during exercise and to promote recovery afterward, preventing proteins from being lost and muscle mass from decreasing. Carbohydrates are the primary source of energy for muscles, especially for high-intensity exercise that relies on anaerobic pathways and the recruitment of Type IIB muscle fibers. Proteins are crucial for muscle repair and growth, facilitating building muscle mass by helping to rebuild muscle fibers that have been stressed during physical activity. Additionally, fats provide a long-lasting source of energy during low-intensity and endurance activities, which is crucial for sustaining muscle strength. Certain vitamins and minerals also play important roles in muscle function. For example, calcium is vital for muscle contraction, and magnesium helps in muscle relaxation and recovery, both of which are important for maintaining muscle protein levels and preventing muscle injury. B vitamins are involved in energy production, helping the body convert carbohydrates, fats, and proteins into usable energy. A balanced diet rich in these nutrients can support sustained exercise performance and optimal recovery.

AG1 by Athletic Greens (Optional)

For those looking to supplement their nutrition, products like AG1 by Athletic Greens provide a convenient way to ensure all the essential vitamins, minerals, and nutrients are included in a daily regimen. While not a replacement for a healthy diet, such supplements can support muscle recovery, energy levels, and overall athletic performance, particularly in response to exercise training when combined with a balanced nutrition plan.

Conclusion

Maximizing muscle performance requires a comprehensive approach that combines proper training, an understanding of muscle fiber types, and targeted nutrition. By focusing on both anaerobic and aerobic energy systems and fueling your body with the right nutrients, you can unlock your full athletic potential and achieve your fitness goals. Whether you're aiming for strength, endurance, or overall muscle development, consistency in training and nutrition is key.

Now that you have a deeper understanding of how muscles work and how to optimize them, it's time to put this knowledge into practice. Start applying these principles in your fitness routine and watch your progress soar. For more tips and guidance, check out the video below:

How Your Muscles Change With Exercise

To continue learning and refining your muscle performance strategies, consider different training techniques that promote the healing of muscle.

If you want to dive deeper into muscle function, structure, and performance, you may also benefit from our full Myology Course, which expands on these concepts in detail.